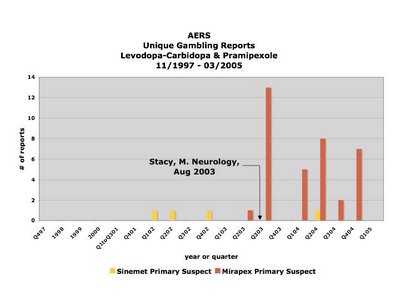

The above is a graph of the distribution over time of the registering of reports linking gambling to either levodopa-carbidopa/Sinemet (yellow) or pramipexole/Mirapex (red) to the FDA's Adverse [Drug] Event Reporting System (AERS) database between November of 1997 and March 2005. The publicizing of the first study purporting to have found an association between pramipexole/Mirapex is denoted in August, 2003, and its effect is clear.

And here is the context for that bar chart.

Ana Szarfman, MD, PhD, P. Murali Doraiswamy, MD, Joseph M. Tonning, MD, MPH, and Jonathan G. Levine, PhD published a research letter to the editor entitled “Association Between Pathologic Gambling and Parkinsonian Therapy as Detected in the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Database” in the Archives of Neurology in February of 2006.

In their letter, Szarfman et al say they found, among other things, 39 reports linking Mirapex to gambling in the FDA's AERS database. They then went on to apply the Multi-item Gamma Poisson Shrinker (MGPS) statistical algorithm to the reporting rates of certain drugs in conjunction with gambling. I am not sure how that works, but Mirapex came out the other end of that algorithm looking guiltier than ever.

However, what Szarfman et al failed to reveal was that all but one of the reports in question regarding Mirapex were registered after the first study purporting an association between it and gambling was publicized heavily by the AAN in August of 2003 (Stacy, Driver-Dunckley. Neurology, August 2003).

The fact that Szarfman et al chose not only not to reveal but also not to take what is known as "the publicity effect" into account, particularly one of such magnitude (there was a virtually 100-fold increase in the reporting rate starting immediately after the publicizing of the study in 2003, and this was after extensive clinical trials and six years on the market with only one gambling report) is at odds with a recommendation she and her co-authors make in their 2005 paper entitled “Perspectives on the Use of Data Mining in Pharmacovigilance,” in which they say:

"Publicity resulting from advertising, litigation or regulatory actions (e.g. "Dear healthcare provider" letters and product withdrawals) may result in increased reporting and can generate higher-than-expected relative RRs.[reporting ratios][56,58] Relative RRs should be examined over time in hopes of detecting these influences, although there are no definitive criteria for using data-mining techniques to reliably identify such effects."In this case, the number of reports is so small number and they were registered over such a short period of time that there was no need to use data-mining techniques to detect this effect. In fact, it would be impossible not to see such a sudden skyrocketing in reporting as this, if one were in possession of the data - as I am, having requested it directly from the FDA when Dr. Szarfman declined to provide me with the dates the reports were registered.

Consequently, is difficult to interpret it as anything but disingenuous when Szarfman et al state in their conclusion that the reports stimulated by the reporting of the case series from the 2003 study to the AERS may have increased the MGPS signal scores. It would be difficult to argue against the statement that the stimulated reporting was the MGPS score, and that in fact without it, there would be no MGPS score for Mirapex at all.

If anyone wants to go through the raw data, please contact me – I would be very happy to send it to you – or my refined data – yours for the asking. The dates of the reports don’t lie.